History of the Medal

"Courage isn’t a brilliant dash A daring deed in a moment’s flash; It isn’t an instantaneous thing Born of despair with a sudden spring.

But it’s something deep in the soul of man That is working always to serve some plan."

-Edgar A. Guest

“Honorary Badges of distinction are to be conferred on the veteran Non-commissioned officers and soldiers of the army who have served more than three years with bravery, fidelity and good conduct; for this purpose a narrow piece of white cloth of an angular form is to be fixed to the left arm on the uniform coats;

Non-commissioned officers and Soldiers who have served with equal reputation more than six years, are to be distinguished by two pieces of cloth set in parallel to each other in a similar form..."

Hasbrouck House, Newburgh, New York, Wednesday, 7 August 1782.

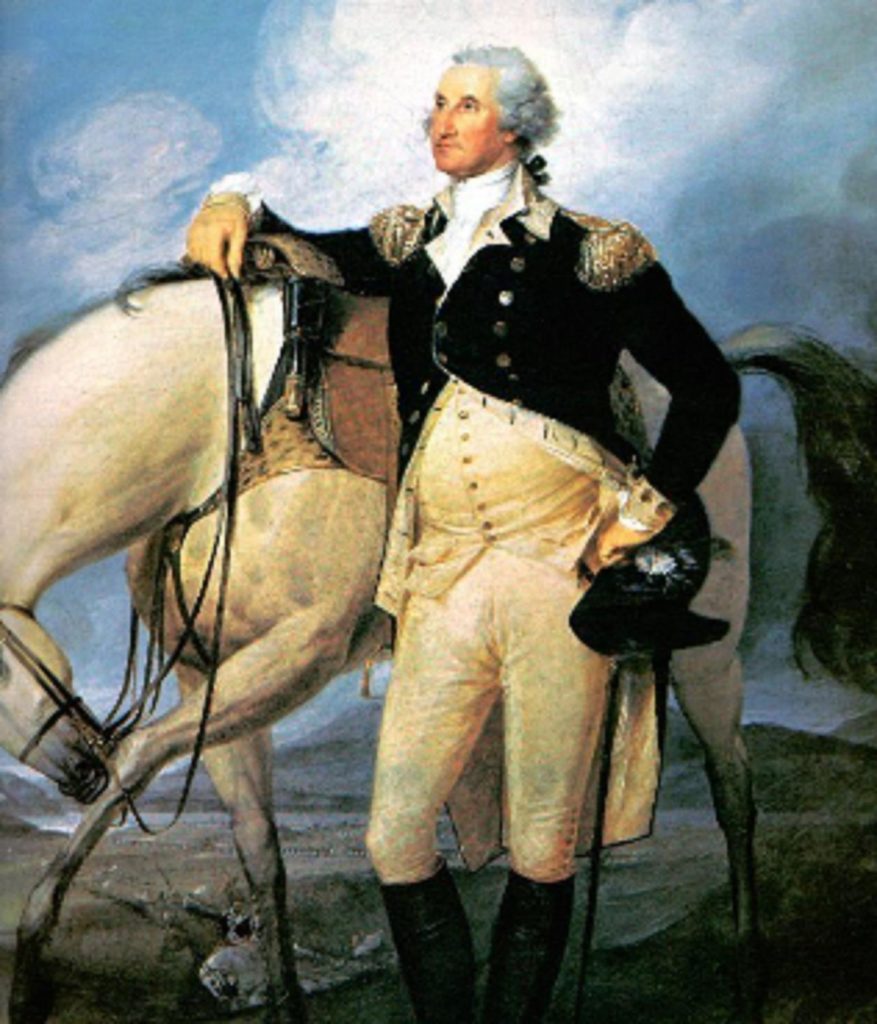

George Washington, the Commander in Chief of the Continental Army, sat at his desk in what

had once been the Hasbrouck family kitchen. The intense summer heat was relieved only by the gentle breeze from the Hudson River about 400 yards away. This

grey dressed stone and rubble Dutch vernacular style house had served as Washington’s headquarters since 31 March when he had returned north to the strategic

Hudson Highlands after his victory at Yorktown.

By 7 August 1782, hostilities had ended and peace talks were under way in Paris. That day, George Washington’s thoughts were with his men camped nearby at New Windsor. They had suffered appalling privations for over six years. His officers were on the verge of mutiny because of lack of pay, rations and supplies withheld by a corrupt and negligent Congress. Worse, Congress had taken away the authority of his general officers to recognize their soldiers’ courage and leadership by awarding commissions in the field. Congress simply could not afford to pay their existing officers let alone any new ones. As a result, faithful service and outstanding acts of bravery went unrecognized and unrewarded. George Washington was determined to end that. So from his headquarters perched 80 feet above the Hudson, he issued a general order establishing the “Badge of Distinction” and “Badge of Merit.”

Badge of Merit

The General, ever desirous to cherish a virtuous

ambition in his soldiers, as well as to foster and encourage every species of military merit, directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is

performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings, over his left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with

narrow lace or binding. Not only instances of unusual gallantry, but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way shall meet with a due

reward….The road to glory in a patriot army and a free country is thus opened to all. “Thus, George Washington established the “Badge of Merit”. In its

shape and color, the Badge anticipated and inspired the modern Purple Heart. In the exceptional level of courage required to be considered for the Badge,

however, it was the forerunner of the Medal of Honor.

The General, ever desirous to cherish a virtuous

ambition in his soldiers, as well as to foster and encourage every species of military merit, directs that whenever any singularly meritorious action is

performed, the author of it shall be permitted to wear on his facings, over his left breast, the figure of a heart in purple cloth, or silk, edged with

narrow lace or binding. Not only instances of unusual gallantry, but also of extraordinary fidelity and essential service in any way shall meet with a due

reward….The road to glory in a patriot army and a free country is thus opened to all. “Thus, George Washington established the “Badge of Merit”. In its

shape and color, the Badge anticipated and inspired the modern Purple Heart. In the exceptional level of courage required to be considered for the Badge,

however, it was the forerunner of the Medal of Honor.

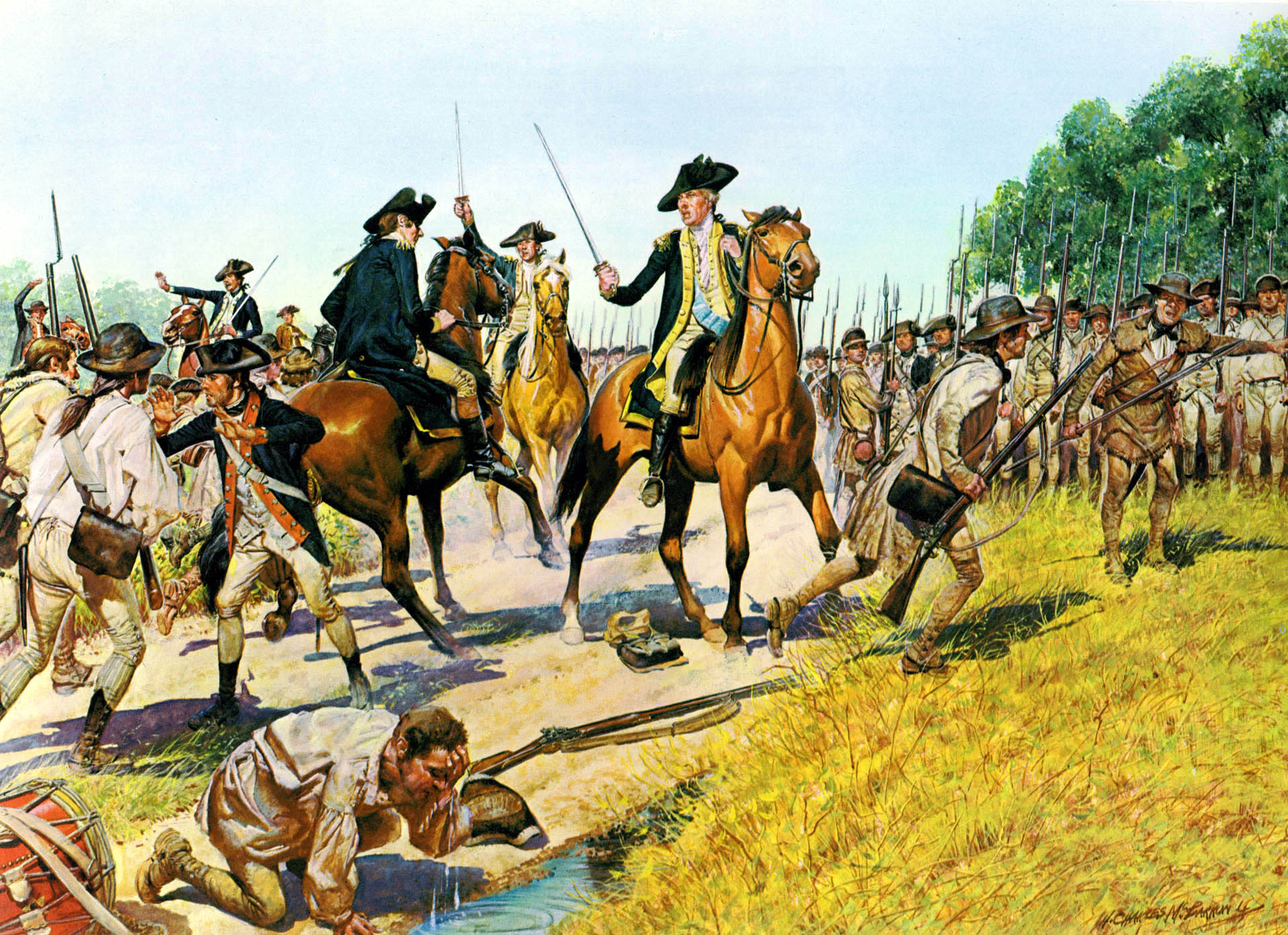

In his book “Almost a Miracle”, historian John Ferling writes that “the forlorn conditions under which America’s soldiers were made to live and campaign was a national disgrace. That the army did not implode in a frenzy of mutinies long before 1781 was little short of miraculous.” Professor Ferling is correct. Never in modern military history has an army been so cruelly abused by its political masters.

Washington Camp

It was bad enough that these

citizen soldiers had to face the formidable force of the professional British army. What was worse was that they faced the harrowing experiences of

eighteenth century warfare – the agony of long marches, the debilitating illnesses, the appalling casualties – without the proper weapons, often

without boots, winter coats or food.

It was bad enough that these

citizen soldiers had to face the formidable force of the professional British army. What was worse was that they faced the harrowing experiences of

eighteenth century warfare – the agony of long marches, the debilitating illnesses, the appalling casualties – without the proper weapons, often

without boots, winter coats or food.

The memoir of Private Joseph Plumb Martin, who left his grandfather’s Connecticut farm in 1775 and served for eight years in the Continental army, has left us a grim, vivid description of how bad conditions truly were. In January 1780, for example, his unit took up a position in Westfield, New York prior to mounting an attack on a British fort on Staten Island. Private Martin writes: “we…took up our abode for the night upon a bleak hill, in full rake of the northwest wind, with no covering or shelter than the canopy of the heavens and no fuel but some old rotten nails which we dug up through the snow which was two or three feet deep… we were absolutely, literally starved…I saw several of the men roast their old shoes and eat them.” He added: “Here was the army starving and naked, and there their country sitting still and expecting the army to do notable things while fainting from sheer starvation.” The reason why Private Martin and his comrades were starving and unprotected against the bitter winter cold was the outrageous corruption and profiteering surrounding the army’s supply chain which Congress failed to address throughout the war.

George Washington was acutely aware of the suffering endured by his troops. The Commander in Chief was, of course, a strict and sometimes ruthless disciplinarian. He had to be. But Washington was also a compassionate military manager deeply devoted to the well-being of his enlisted men. If you read his papers, you come away impressed by the almost superhuman energy he devoted to improving the health and welfare of his troops and to lobbying Congress and the States for the food and other supplies they had promised him. No detail was ever too small for him to attend to if it improved the life of an enlisted man.

Washington was indomitable usually

working at least 12-14 hours per day, but his task throughout the war was monumental. He had to transform thousands of brave, inexperienced and

undisciplined citizen soldiers into an effective fighting force capable of fighting a conventional as well as a guerilla war. Moreover, the Commander

in Chief also had to create an effective intelligence service that would deliver accurate, actionable information on the enemy’s capabilities and

intentions, persuade Congress and the States to deliver the supplies they had promised him and work effectively with the French who had different

strategic objectives. Add to that the constant political interference in the appointment and promotion of officers and the corruption and profiteering

in the supply chain and you begin to understand the appalling burdens that sat upon Washington’s shoulders for over seven years.

Washington was indomitable usually

working at least 12-14 hours per day, but his task throughout the war was monumental. He had to transform thousands of brave, inexperienced and

undisciplined citizen soldiers into an effective fighting force capable of fighting a conventional as well as a guerilla war. Moreover, the Commander

in Chief also had to create an effective intelligence service that would deliver accurate, actionable information on the enemy’s capabilities and

intentions, persuade Congress and the States to deliver the supplies they had promised him and work effectively with the French who had different

strategic objectives. Add to that the constant political interference in the appointment and promotion of officers and the corruption and profiteering

in the supply chain and you begin to understand the appalling burdens that sat upon Washington’s shoulders for over seven years.

It was understandable that it was not until after Congress took away the power to grant commissions in the field and the war was winding down in August 1782 that the Commander in Chief had the time to devise ways to honor the courage of his enlisted men and non-commissioned officers. George Washington’s decision to create two awards exclusively for enlisted men and non-commissioned officers was unprecedented. Neither the British nor any other European army had decorations for anyone other than their officers. But Washington believed passionately in the republican ideals of the revolution, and he also understood that his continentals were the first people’s army of patriotic volunteers who had fought for these ideals and who had been pushed to the outer limits of human endurance during the war.

Washington was committed to honoring his troops, but the idea for the “Badge of Military Merit” was probably Baron Von Steuben’s. The tough Prussian general may have had difficulty in instilling military discipline and order into the Continental army, but he admired their courage and fighting spirit. As a veteran of European wars, he would have been aware that the Czar of Russia had created the Cross of St. George for Gallantry and it is reasonable to speculate that he wanted the Americans to have a similar award for gallantry.

If we do not know for sure who inspired the “Badge of Military Merit”, we are even less sure about who designed it. Speculation runs from Pierre L’Enfant, later the architect of Washington DC, to Martha Washington or even General Washington himself. We will never know the truth. The original badge was made of purple silk edged with silver colored lace or binding on a wool background. One was embroidered with a leaf design; another – Sergeant Elijah Churchill’s – has the word “merit” crocheted into the fabric. The heart symbolized courage and devotion. Purple was associated with royalty and would stand out on any uniform.

To determine who should receive the badge, Washington ordered that a board of military officers be convened whenever the Adjutant General had recommendations for them to consider. This board never met because the Adjutant General never supplied any recommendations. Given the brewing mutiny among the officer corps at this time, it is reasonable to speculate that the Adjutant General offered no recommendations because he never received any. Preoccupied with their own pay and pension problems, too many officers had too little time to worry about writing recommendations for this new gallantry medal for their soldiers. By April 1783, when the Commander in Chief had received no recommendations for the “Badge of Military Merit” and when news of the peace agreement reached headquarters, Washington demanded immediate action before the Continental Army began to disband. On 17 April 1783, Washington ordered that a new review board be created and he demanded and got immediate results within days. The new board recommended two candidates: Sergeant Elijah Churchill, Fourth Troop, Second Troop of Light Dragoons and Sergeant William Brown of the 5th Connecticut regiment. A little later, they recommended a third candidate: Sergeant Daniel Bissell of the 2nd Connecticut regiment, one of Washington’s most important and successful spies. It is, however, possible that Washington himself recommended Bissell.

All three were superb choices. The first recipient was Sergeant Elijah Churchill from the 4th Troop, 2nd Regiment of Light Dragoons which had conducted some of the most daring and spectacular raids of the Revolutionary War. Sergeant Churchill received the “Badge of Merit” in recognition of his leadership in two commando-style raids. The first was on 23 November 1780 against Fort St. George on Long Island when he led the advance team. He surprised the British defenders, captured and destroyed the fort. The goal of the mission had been to destroy a storage depot which housed several hundred tons of much needed hay for winter forage for British army horses. Fort St George protected the forage depot and so the capture and destruction of the fort made a vital contribution to the success of the mission. The second raid for which Sergeant Churchill was honored occurred a year later in October 1781 while the main army was at Yorktown. Once again, Sergeant Churchill led the advance party this time against Fort Slongo on the north shore of Long Island. And once again Sergeant Churchill’s bold leadership of the advance party surprised the British defenders and led to the capture of a large quantity of enemy supplies. These and other daring raids not only kept the British off-balance unsure whether Washington was going to try to recapture New York, but also forced British commanders to detach large numbers of troops from their over-stretched army to reinforce isolated and exposed outposts.

The second recipient of the Badge of Merit was Sergeant William Brown from the 5th Connecticut regiment. George Washington honored Sergeant Brown for his extraordinary heroism at the Battle of Yorktown. There, on the night of 14 October, Sergeant Brown led the advance party of Lieutenant Colonel Alexander Hamilton’s troops against British Redoubt No 10, one of two key strongholds protecting the British inner defense line at Yorktown. Without waiting for the sappers and pioneers to clear away the sharpened trees designed to impale attacking troops, Sergeant Brown led his men on what could easily have been a suicide mission. To help ensure silence and surprise they attacked with unloaded muskets. Armed only with bayonets, Sergeant Brown and his advance party ran over a quarter of a mile climbed over the sharpened trees and charged the redoubt. Despite a murderous hail of musket fire, they and the remainder of Hamilton’s troops overcame the defenders in ten minutes of intense fighting.

The third recipient of the Badge of Merit whose exceptional heroism can be documented was Sergeant Daniel Bissell of the 2nd Connecticut regiment, one of George Washington’s bravest and most successful spies. In August 1781, acting under direct orders from the Commander in Chief, Bissell posed as a deserter and joined Benedict Arnold’s Corps of loyalists in New York City. From 14 August 1781 to 29 September 1782, Bissell served as a quarter master sergeant for Arnold. He used his position to gather a vast amount of information on British troop strength and deployments in and around New York. He recorded these in a series of notes and memoranda that he planned to send or bring to Washington. Every moment of every day for over a year, Bissell’s life hung by a thread. One wrong move, one mistake and he would have been executed as a spy.

When British military intelligence began to suspect that there were American sleeper agents in their midst, the British commander in chief ordered that any soldier found with military documents would be regarded as a spy. Bissell destroyed all of his memoranda but only after committing every detail to memory.

When he escaped from New York and reached headquarters in Newburgh, he was able to dictate his intelligence to Lieutenant Colonel David Humphreys, Washington’s aide de camp. If Washington had decided to attack the British in New York rather than at Yorktown, Bissell’s intelligence would have been vital.

We know for sure that Sergeants Churchill, Brown and Bissell received the Badge of Military Merit. Recent research by the Military Order of the Purple Heart’s National Americanism officer, Ron Siebels, shows that Peter Shumway, John Sithins and William Dutton, three other soldiers in Washington’s Continental Army, also received the Badge of Military Merit. But we do not yet know the exceptional acts of courage for which they were honored. It is possible that there were other candidates and other recipients. But we will never be sure unless the “Book of Merit” (in which all of the recipient’s names and heroic deeds were to be recorded) is found. But it has been missing for over two centuries.

Unfortunately, we also do not know for sure

whether Washington presented Sergeants Churchill and Brown with their honors personally. We do know from Sergeant Bissell’s pension records that his Badge

of Military Merit was presented to him on the lawn at Hasbrouck House by Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Trumbull, Washington’s Military Secretary. Although

Washington intended the Badge of Military Merit to be made permanent, it was allowed to lapse after the army was disbanded in June 1783. At the end of the

Revolutionary War, no federal decoration was awarded to American servicemen until the Navy Medal of Honor was created in 1861 during the Civil War.

Unfortunately, we also do not know for sure

whether Washington presented Sergeants Churchill and Brown with their honors personally. We do know from Sergeant Bissell’s pension records that his Badge

of Military Merit was presented to him on the lawn at Hasbrouck House by Lieutenant Colonel Jonathan Trumbull, Washington’s Military Secretary. Although

Washington intended the Badge of Military Merit to be made permanent, it was allowed to lapse after the army was disbanded in June 1783. At the end of the

Revolutionary War, no federal decoration was awarded to American servicemen until the Navy Medal of Honor was created in 1861 during the Civil War.

Professor Ray Raymond MBE, FRSA

State University of New York

Professor Ray Raymond MBE, FRSA, served 21 years in Her Majesty’s Diplomatic Service as a special adviser to HM Director General of Trade and Investment for the USA and worked extensively with senior members of the British Royal Family. From 1997 to 2005, he advised the Chief of Staff to British Prime Minister Tony Blair on US politics and public policy. In 2000, he was honored by Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, and in 2010 was honored by HRH the Duke of York for efforts to strengthen the relationship between the City of London and Wall Street.

Professor Raymond teaches Government, International Relations and History at the State University of New York. Concurrently, he lectures on Comparative Politics and International Relations at the US Military Academy, West Point. In 2006 received the Outstanding Civilian Service Medal from the Department of the Army for his contributions to the academic program at West Point. He has also served as a consultant to the US Air Force Academy and has lectured at the US Army War College, the US Naval Academy, the United Kingdom’s Joint Services Defense Academy and Royal United Services Institute.

On Behalf of the Military Order of the Purple Heart, in 2007 Professor Raymond wrote “George Washington and the Badge of Military Merit,” and was the lead author of “Some Gave All,” a special publication to mark the 75th anniversary of the MOPH. He has written extensivley on the history of US foreign policy towards the United Kingdom, ethnic nationalism, terrorism and the United Nations. He is currently working on a diplomatic biography of John Jay.